This is the third in a series of brief papers designed to share lessons learned from a five-year community-based primary healthcare innovation project. In this paper, we discuss how the implementation of the pop-up events was guided by an ecological model that prioritized outreach, community development, and the sharing of space and resources.

Innovative Models Promoting Access-to-Care Transformation (IMPACT) was a five-year (2013-2018), CIHR-funded participatory research project to enhance access to primary healthcare (PHC) for vulnerable populations. Local Innovation Partnerships (LIPs) were developed in communities where access issues were identified. Set in three Australian states (New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria) and three Canadian provinces (Alberta, Ontario and Québec), each LIP was created to (1) identify vulnerabilities and access issues faced by local communities and (2) design and implement an innovative intervention to enhance access to care. To learn more about IMPACT visit www.impactresearchprogram.com

Introduction

The Alberta project team identified the region of north Lethbridge where people are underserved by, and struggle to connect with, primary healthcare services. Working closely with stakeholders, members of the Alberta LIP identified engagement with, and approachability of, PHC services as key access issues that should be addressed by an intervention. The team designed and implemented a series of pop-up health and community services events that brought together PHC service providers to different locations in North Lethbridge.

Given unlimited resources, our community partners said the best way to address the needs of north Lethbridge residents would be to put a clinic in an easy-to-reach location in north Lethbridge. They suggested this clinic could also house service providers from non-health sectors, such as foodbanks, newcomer services agencies, and other social services organizations. However, the research program did not have unlimited resources for the intervention nor were there sufficient community resources to acquire a dedicated space. Therefore, a “bricks and mortar” solution was not feasible. There were, however, other ideas for enhancing access identified by our community partners that were feasible.

Our community partners clearly identified the need for the intervention to haveservices located in North Lethbridge, with a broad range of services being offered in one place at the same time. We were also told that the most vulnerable often lack trust in healthcare services due to previous experiences feeling less than welcomed, respected, or cared about when accessing services. Therefore, we knew that any intervention had to bring PHC services to where people are and ensure any services provided were approachable, welcoming, and engaging. Our partners also said that being welcoming meant that no one should be turned away if they needed services. We therefore purposely did not target specific populations or groups and welcomed anyone wanting to attend the pop-ups.

Changing the way we think about enhancing access

As we discussed how to design the pop-up to best meet identified needs, a set of shared principles about the needed approach emerged that were grounded in our commitment to not re-marginalize people through the process of providing care. These principles included working together differently, meeting people where they are, and prioritizing relationships. We also knew that we wanted service providers to provide services and not just information, and to use existing space and resources.

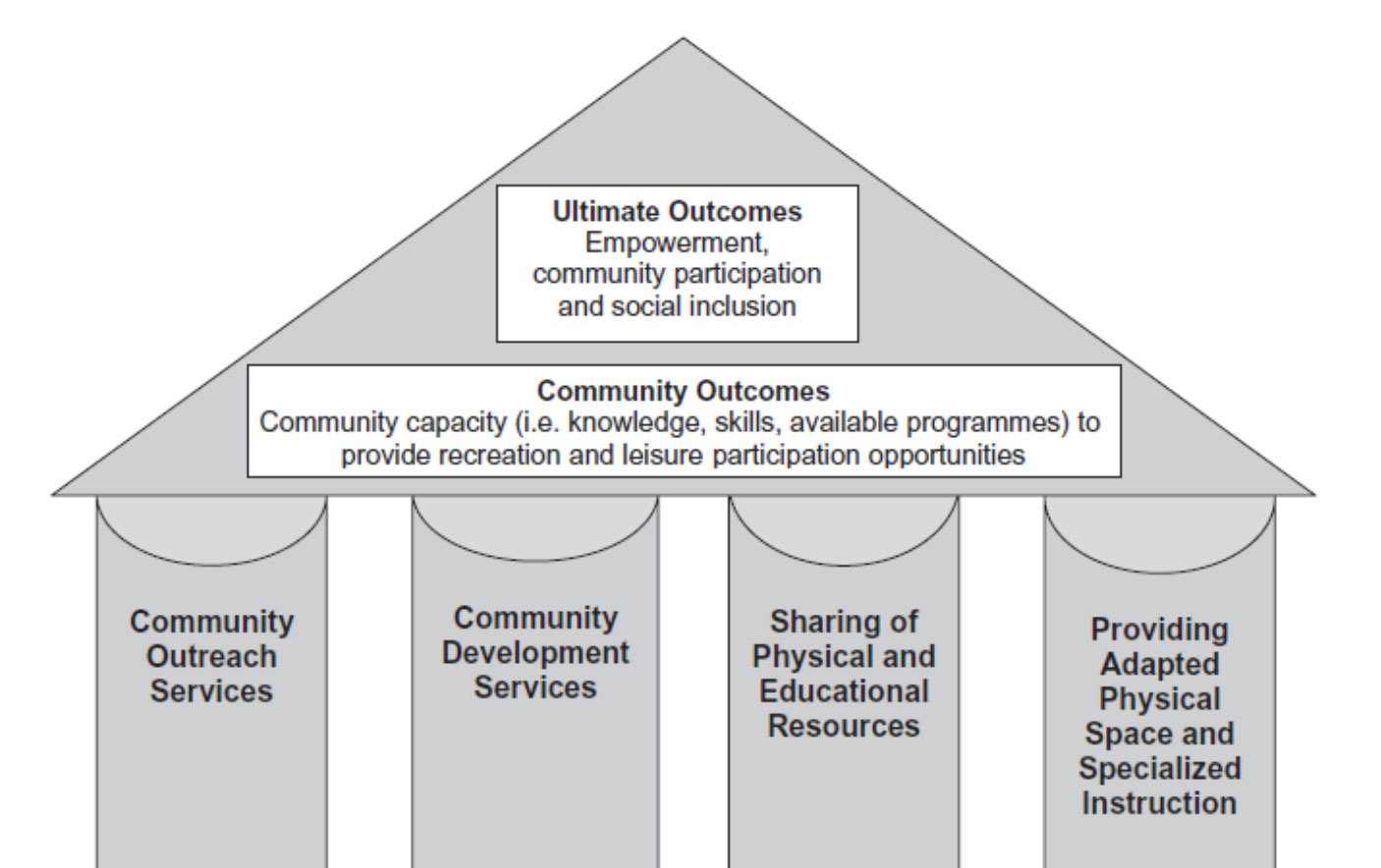

A model proposed by King et al. (2012) informed and expanded our principles and goals to provide care and share space and resources. The creators of this model prioritized outreach, community development, the sharing of resources, and adapting space (which may progress to building necessary foundational infrastructure when bricks and mortar solutions become feasible). King et al. (2012) also suggested that care be provided within a supportive community context. They argued that having care provided in a community setting, and with community participation, builds community knowledge and capacity to understand and meet the needs of the population. When a community views care holistically and inclusively, not just for a specific group or population, there is reduced risk of marginalizing people accessing care.

Applying this model helped us guide discussions within the LIP about what each organization was already doing to address PHC needs in north Lethbridge, how that could look differently using a coordinated outreach model, and what resources each could share in a joint effort to meet needs.

Figure 1. From: King et al., (2012)

How did the King et al. model help us with the implementation of the pop-ups? The following are lessons learned from implementing the pop-up events in North Lethbridge:

- Outreach – The model supports delivery of services where people are. This aligned well with the pop-up model, as well as our goal to always provide a service and not just information (i.e., true outreach services). We wanted the pop-ups to be about providing services and not shift into the realm of “health fairs,” where information is given but few services are provided. Providing outreach services was not typical of day-to-day work for some services providers, but as the pop-ups proceeded, service providers found creative ways to provide their services at the pop-ups.

- Community Development – The ecological model stresses the importance of connection within a community to

identify and understand the needs of a community. In the case of the pop-ups, the connection happened at the

following levels:

- Connection between stakeholders – Through deliberative forums, the early stages of the pop-up work brought together key stakeholders to identify access issues and ways to tackle them. Stakeholder included leaders, managers, and frontline workers from health and community services organizations, as well as north Lethbridge residents and other interested parties. The deliberative forums provided an opportunity for stakeholders to get to know each other, build connections, and strategize on how best they could work together to enhance care for residents of north Lethbridge. The deliberative forums provided the foundation for all subsequent community and relationship building.

- Connection between service providers – We encouraged service providers to attend rehearsal events prior to each pop-up. The rehearsals focused on service providers getting to know each other and the services they provide, their experiences serving vulnerable populations, and how to provide care that was more welcoming and engaging. The relationships between service providers that were established at the rehearsals helped with warm handoffs from service to service at the pop-ups. This warm handoff shifted from the typical healthcare approach of “Go and see this service provider” to “I’m going to take you to meet Jane from Identification Services, and she may be able to help you with some of your other needs.”

- Connection between service providers and persons accessing care – Attending the pop-ups allowed service providers to see and appreciate the unmet PHC needs of residents of north Lethbridge. We also encouraged service providers to prioritize relationships and engagement with people accessing care at the pop-ups, which led to a deeper understanding of these needs. We provided service providers with tools like “How’s your 5?” ¹ [Mercy Health (2018)] to help facilitate meaningful conversations and interactions with people accessing services. With a better understanding of needs, service providers were able to recommend other services to those needing care, which led to increased access of services.

- Sharing of space and resources - The ecological model reminded us that a lot can be done when we think differently about space and “what we need in order to provide care”. Challenging service providers to share space and resources affected how service providers worked together and provided care. Indeed, service providers consistently mentioned the value of having multiple service providers in one location, and they often collaborated or sought the expertise of others to ensure attendees of the pop-ups access to the care they needed. As a result of sharing space and resources, service providers became more aware of services in the community, formed relationships with other service providers, and collaborated to provide care. Sharing space and resources provided an opportunity for service providers to work beyond their silos and contribute to a culture that enhanced relationships and connection for comprehensive services.

¹How’s Your 5? creates a common language to support each other across five fundamental domains of human experience: Work (employment/school), Love (relationships/social support), Play (selfcare/joyful activities), Sleep (sleep habits), and Eat (consumption – eating and drinking). (http://www.unitedhoumanation.org/blog/uhn-partners-with-mercy-family-center-to-launch-hows-your-5-iniative; https://www.mercy.net/practice/mercy-family-center-metairie/hows-your-5/)

WHAT WE LEARNED…

The model proposed by King et al. (2012) provided a guiding structure for the design and implementation of the pop-ups. It also provided an important reference point for us and our partners throughout the research project. We focused our work around the model’s aims of community outreach, community development, and sharing of space and resources. In so doing, we enhanced access to care without the need for a “bricks and mortar” solution.

References Download all Papers

Citation

Perrin S, Mallard R, Barnes J, Spenceley S, Scott C, Lundy C, Donahue S, Andres C on behalf of the IMPACT team. (2019). Launch & Learn Paper 3: Starting with community: foundations for enhancing access. Available from https://policywise.com/services/evaluation/launch-learn/

For More Information

Cathie Scott, PolicyWise for Children & Families cscott@policywise.ca