This is the fifth paper in the series and will highlight the value of embedding cycles of learning throughout implementation, providing a foundation for implementing community-based healthcare interventions in complex contexts.

Innovative Models Promoting Access-to-Care Transformation (IMPACT) was a fiveyear (2013-2018), CIHR-funded participatory research project to enhance access to primary healthcare (PHC) for vulnerable populations. Local Innovation Partnerships (LIPs) were developed in communities where access issues were identified. Set in three Australian states (New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria) and three Canadian provinces (Alberta, Ontario and Québec), each LIP was created to (1) identify vulnerabilities and access issues faced by local communities and (2) design and implement an innovative intervention to enhance access to care. To learn more about IMPACT visit www.impactresearchprogram.com

Introduction

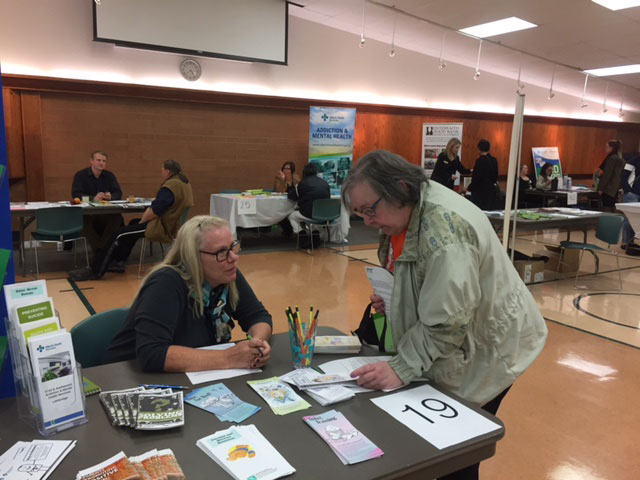

The Alberta project team identified the region of north Lethbridge where people are underserved by, and struggle to connect with, primary healthcare services. Working closely with stakeholders, members of the Alberta LIP identified engagement with, and approachability of, PHC services as key access issues that should be addressed by an intervention. The team designed and implemented a series of pop-up health and community services events that brought together PHC service providers to different locations in North Lethbridge.

WHERE DOES CREATIVITY FIT?

Canadian healthcare systems are complex and in a constant state of change. Over the last decade, a great deal of attention has been focused on improving access to communitybased primary healthcare (CBPHC). Given the complexity of the systems and the influence of context, designing interventions to improve access to PHC services is challenging. Typically, research on implementation of interventions focuses on gathering information by following a series of predictable, detailed, and well-executed steps through each stage of development, design, implementation, and evaluation, leaving little room for creativity or sensitivity to context. All too often, the solutions to problems focus only on the outcomes, losing sight of the lessons learned throughout the process, and ignoring what did not work.

More prescriptive methods work well for experimental research designs but when evaluating human-centred research that is dynamic, somewhat unpredictable, and highly influenced by context, more adaptive strategies are needed.

A developmental evaluation (DE) approach, conceptualized by Patton (2011), is an approach to evaluation that considers dynamic and unpredictable contexts by encouraging reflective feedback loops that support ongoing, adaptive decision making. The beauty of a DE is that it supports learning throughout each stage of research and creates opportunities to learn from trial and error.. Recognizing the influence of context on strategies to enhance access required us to be open to alternatives, but also required a change in our understanding and language.

Rather than talking about best practices, we fully embraced the notion of learning from innovations in the community and encouraged people to think in terms of leading, promising, and emerging practices (Health Council of Canada, n.d.).

Below are some of the key concepts that guided our application of DE and the approaches the research team used to reflect those concepts.

We acknowledged that we did not have a clear understanding of all processes

Approach: Relinquishing power and control and practicing humility. Community consultations with service providers allowed for expertise and knowledge to flow from the community. Taking advantage of the capacity that already existed in the community supported shared decision making that was informed through creative and thought-provoking discussions about vulnerable populations, service delivery, and unmet needs. This approach facilitated the research team in working alongside service providers, sharing the pop-up experience, and being careful observers and listeners.We adapted design and implementation strategies in real-time

Approach: Prioritizing the capacity of the system to learn. It was important to develop versatile strategies and evaluative tools that would support an iterative and collaborative feedback process. After Action Reviews (Collison et al., 2004) were a tool used by the Alberta LIP to collect feedback from service providers after each pop-up. The feedback was used to tailor the intervention to better meet the needs of both service providers and the people accessing care each time it was delivered. Although our attention remained focused on outcomes, the lessons we learned in the process and our commitment to being flexible enough make changes were equally, if not more, valuable. In addition, rather than prescribing strict practices, the iterative process allowed for practice change to evolve organically by provoking careful reflection by service providers on their own service practices.We recognized the importance of context

Approach: Not being afraid to make mistakes. Human-centered research takes place in contexts that are constantly changing. This is especially important to consider when an intervention spans several years and includes diverse and complex populations, organizations, and systems. During community consultations it was evident that not all organizations were ready to participate in this intervention. Embracing the complexity and dynamic nature of community-based health care allowed the Alberta LIP to move forward without having all the answers and with organizations that were ready.We embedded ongoing sharing of knowledge throughout the intervention

Approach: New understandings often emerged from regular meetings with members of the Alberta LIP. The insights gained evolved from discussions about both what worked and what did not. Being able to be reflexive and look through a critical lens also applied to our own biases, behaviors and preconceived notions of what success looks like. Sharing the quantitative and qualitative data and what we were learning at each pop-up in a timely manner with service providers created a shared awareness of what happened at each event and opportunities for creative discussions about how to continue to improve the delivery of services.We focused on relationships

Approach: Building creativity and responsiveness into the research process. The feedback from participants in the early pop-ups identified the need for a more welcoming atmosphere and more meaningful engagement with attendees. Without the iterative feedback and resulting discussions, we might have missed that providers were still practicing in a “business as usual” way that did not necessarily facilitate opportunities to really connect with attendees at the pop-up. For example, providers continued to sit behind tables, waiting for patients to come to them and often spoke to patients as they would in their service settings. Adapting the intervention to encourage more meaningful connections included a canvas mural art project as a central aspect of each pop-up. The art project provided a less formal opportunity to engage with pop-up attendees and also encouraged service providers to come out from behind their tables to meet with patients at the pop-up. Creative engagement also included implementing the How’s Your 5? strategy which is a conversational tool that assists in getting beyond the conditioned responses to the question, “how are you?”

Approach: Building creativity and responsiveness into the research process. The feedback from participants in the early pop-ups identified the need for a more welcoming atmosphere and more meaningful engagement with attendees. Without the iterative feedback and resulting discussions, we might have missed that providers were still practicing in a “business as usual” way that did not necessarily facilitate opportunities to really connect with attendees at the pop-up. For example, providers continued to sit behind tables, waiting for patients to come to them and often spoke to patients as they would in their service settings. Adapting the intervention to encourage more meaningful connections included a canvas mural art project as a central aspect of each pop-up. The art project provided a less formal opportunity to engage with pop-up attendees and also encouraged service providers to come out from behind their tables to meet with patients at the pop-up. Creative engagement also included implementing the How’s Your 5? strategy which is a conversational tool that assists in getting beyond the conditioned responses to the question, “how are you?”Our approach was guided by a commitment to principles and values rather than adherence to predetermined processes and procedures

Approach: Continued reflection on the foundational values and principles identified by the community which were: 1) relationships; 2) meeting people where they are at; and 3) working together differently. By continuing to return to the principles that guided the intervention, the focus remained on the learning process and collective impact rather than achieving outcomes. We discovered that service providers often felt a tension between delivering value-based care and volume-based care which was often tied to limitations in resources and the notion that quantity is a more desirable outcome than providing quality care. Additionally, asking providers to meet people where they are at often required that “business as usual practices” be checked at the door and required careful consideration of language used at the pop-ups. Incorporating plain language information became another creative strategy to address the power dynamic between provider and patient and encourage better connections were made between them.

What we learned:

Bringing PHC service providers together to offer services in one location, at one time does not necessarily lead to enhanced access to care or professional practice change. Enhancing access to care requires considering how service providers and people receiving care can better relate and understand one another. We propose that efforts to initiate practice change to improve the provision of care build on a foundation of connection that supports time, dialogue, and openness.

References Download all Papers

Citation

Barnes J, Mallard R, Lundy C, Perrin S, Spenceley S, Donahue S, Andres C, Scott C, on behalf of the IMPACT team. (2019) Launch & Learn Paper 5: Embracing creativity in complex community‐based health research: learning through trial and error. Available from https://policywise.com/services/evaluation/launch-learn/

For More Information

Cathie Scott, PolicyWise for Children & Families cscott@policywise.ca

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License